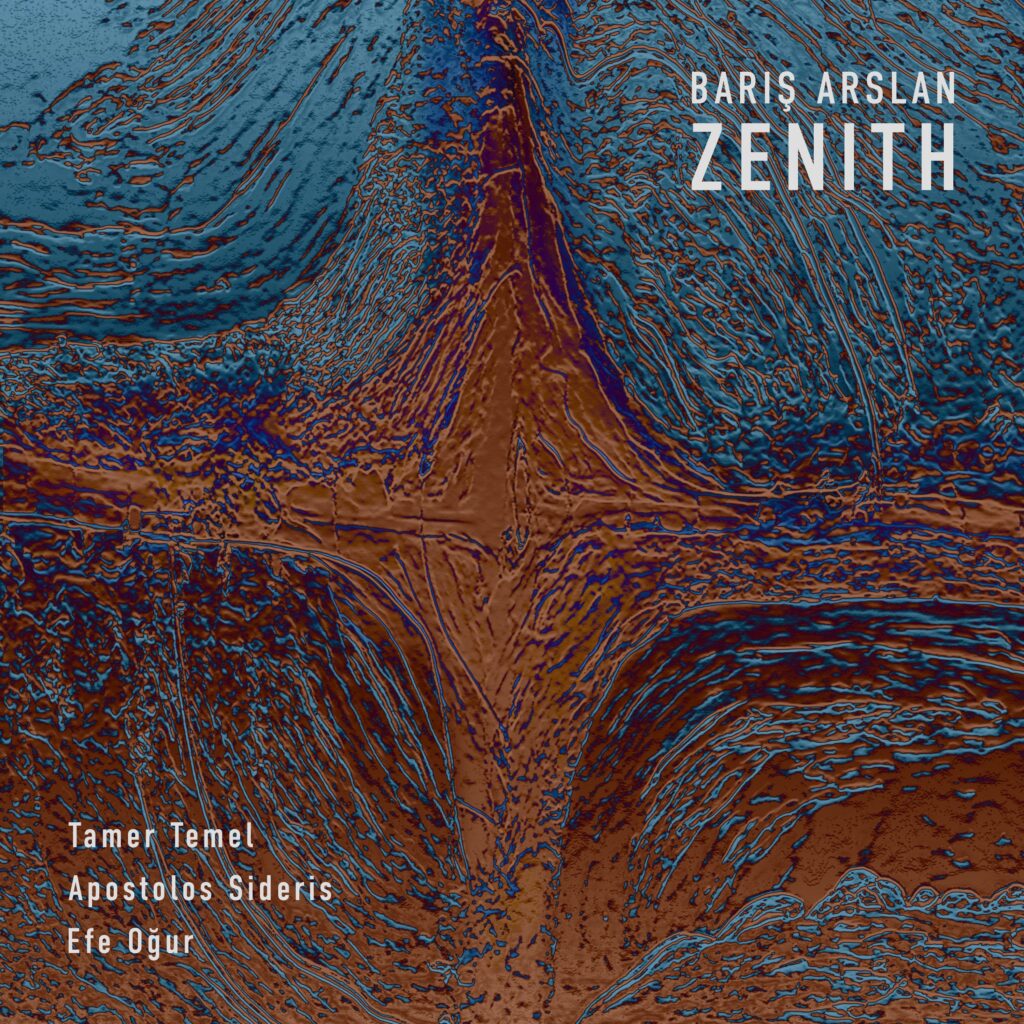

Guitarist Barış Arslan, who has been performing for many years both in Türkiye and internationally, has now presented his debut album Zenith to jazz enthusiasts. This project, shaped by his extensive stage experience and years of dedication, marks a significant milestone in both his personal and musical journey. Known for his unique style that skillfully blends traditional and modern elements, Barış Arslan shares with us insights the album’s creative process. In this exclusive interview, we take an intimate look at the musical path of a jazz musician matured on both domestic and international stages, as well as the story behind his Zenith album.

How do you feel about the Zenith album? What kind of journey has this been for you?

Completing Zenith album means a lot to me. It feels like the first milestone in a long developmental journey that has spanned many years. It’s a moment where I’ve both looked back on the path I’ve walked and questioned what more can be done moving forward. I can definitely say that every aspect of the album process has taught me a lot and changed my perspective on music. If I had known it would have such a strong impact on me, I would have wanted to do it earlier — but life doesn’t always unfold the way you want.

How did the album come to life: When and how was the idea born?

Zenith wasn’t a project that came together all of a sudden; it’s made up of ideas and works I’ve accumulated over the years. It’s the product of a process in which ideas I developed over nearly seven years with Efe Oğur came together to form a story—ideas that contributed to our musical growth. During this journey, many musicians joined our work, and we also had the chance to play with many others. Traces of all of them—their influences and approaches—can be found within Zenith. Seeing the marks left by all the musicians we crossed paths with during this process, especially Efe Oğur, means a great deal to me.

What does the album’s name mean? Does it have a special significance?

The word Zenith refers to the highest point in the sky in astronomy. Symbolically, however, it represents a point one aspires to reach but can never actually attain. What matters is understanding that walking this path—despite knowing it may never be reached—might be one of the most ethical acts a person can strive for. Zenith became a name that, with this awareness, encapsulates the story of the musical journey we’ve undertaken over the years.

We know that all the pieces on the album are yours. Where do you draw your inspiration from?

If I had to answer in one word: everything. Without a doubt, the biggest influence comes from what I listen to. Just like in many other fields, I believe that what comes from tradition is incredibly valuable in music. Feeling and discovering the chain between the past and the present is, in fact, the essence of tradition itself. That’s why it’s important to define the concept of tradition correctly.

Today, many things we call “modern jazz” are actually traditional, and many things we see as traditional are, in fact, modern. So for me, tradition is a living and evolving structure that includes all of these elements. It’s the entire chain that has formed between the past and the present.

In short, despite how it may seem, this process is quite complex and personal. That’s why, instead of jumping to conclusions or criticizing others, I believe the best approach is to observe, feel, and create within this long journey. For that reason, I continue to learn from everything I listen to and draw inspiration from all of it.

Jazz is a very free yet highly disciplined genre. What are the most challenging or most enjoyable aspects of creating within this style?

One of the most defining elements that sets jazz apart from other music genres is improvisation. And in fact, improvisation is a form of storytelling. I believe that when you’re telling a story on stage, you don’t need to be flawless or perfect. What matters is how close you are to reality and to life itself. That feeling of being close to the truth is probably what I enjoy most about this music.

Of course, it’s not easy—sometimes you’re in that space, and sometimes you’re not. But even in both cases, this form of expression keeps you closer to the truth. And maybe, that’s the only thing that truly matters!

As a guitarist, how do you carve out your space in jazz music? How do you balance your playing with other instruments?

The guitar holds a very special place in the history of jazz. In the beginning, it was mainly a rhythmic accompaniment instrument—barely even audible within the orchestra. But as technology advanced and amplification became possible, the guitar began to make its voice heard. With Charlie Christian, it emerged as a lead instrument. Then, through figures like Wes Montgomery, Jim Hall, and Joe Pass, both its harmonic richness and melodic expressiveness became more pronounced. Today, the guitar has evolved into a versatile sound source capable of taking on rhythmic, melodic, and even orchestral roles.

One of the main reasons for this, I believe, is the relationship the guitar has developed with the piano throughout jazz history. Especially in terms of harmonic thinking, the guitar has often tried to surpass its own limitations by modeling the role of the piano. The voicing approach of pianists like Bill Evans had a profound influence on the harmonic language of guitarists. Jim Hall’s chord placement—as if imitating a pianist—and the layered harmonic textures of guitarists like Ben Monder are all outcomes of this influence.

Another recent shift that’s caught my attention is how the practice methods of all instruments have changed. Almost every instrumentalist today is adapting rhythmic practice routines—long common among drummers—to their own instrument. Musicians who didn’t previously practice in a drummer-like fashion now place more importance on such training in order to integrate different rhythmic structures into their improvisation. This has become a form of dialogue not only between guitar and piano but also across drums and all other instruments. These developments broaden the expressive scope of jazz and naturally pave the way for the genre to evolve in new directions.

As a result, in today’s jazz, everyone is interacting with each other’s space more consciously. This brings both responsibility and a great deal of freedom. Within that freedom, it’s important to develop a musical language that carries the knowledge of the past along with the explorations of the present. Perhaps the truest approach is this: being able to tell the same story with musicians who listen to and are attentive to one another. That’s where space and balance really begin—and like everyone else, I’m trying to find myself within that balance.

Which musicians did you work with on this album? Who did the mixing and mastering? How was the studio and recording process?

On the album, I played alongside Efe Oğur (drums), Apostolos Sideris (double bass), and Tamer Temel (saxophone). We’ve been performing together for a long time, and we know each other very well musically. It was a very cohesive team.

The recordings took place at Istanbul Technical University’s MIAM (Center for Advanced Studies in Music). The recording and mixing process was handled by Oğuz Öz, while the mastering was done by Dan Millice.

Throughout the recording, we tried to preserve the liveliness and natural feel of performing on stage. As is well known, there’s a significant difference between playing jazz live and recording it. A live performance is fueled by the energy of the moment, the acoustics of the space, and the direct connection with the audience. What emerges in that moment isn’t just the notes being played. It’s also the audience’s response and the communication between the musicians. These elements make the music unique and unrepeatable.

In the studio, much of that context disappears. Recording takes place in a more controlled environment and requires an inward focus rather than direct interaction. This is both an advantage and a limitation. The advantage is that you can express certain ideas more clearly and focus on details. On the other hand, the spontaneity of taking risks in the moment and the musical surprises that arise from uncertainty can be more subdued.

That’s why, when recording jazz, the goal isn’t just to play correctly—it’s to remember that you’re still making live music. With this album, we tried to bring the sense of listening, interaction, and energy that we create on stage into the studio as much as possible.

In jazz albums, there are usually two types of recording processes: one where musicians go straight into the studio and then perform the pieces over time, and another where they play together extensively before recording. Which approach did you take, and which do you think is more advantageous?

We recorded the album after playing the pieces together for a long time. The compositions on the album evolved over the years on stage—they deepened with each performance and gradually found their own path. Throughout this process, the rhythmic structures, dynamics, and even the form of some pieces naturally took shape. Each musician, especially Efe Oğur, gradually embedded their own voice and approach into the music. So when we entered the studio, it wasn’t about trying something brand new. We were capturing something that was already alive.

The biggest advantage of this method is that the internal balance of the group forms much more naturally. We knew each other not only musically, but personally as well. We knew when to create space and when to step back.

Of course, going straight into the studio and capturing the energy of the moment can also be incredibly valuable. But with this album, we finally recorded music that had been simmering on stage for a long time. It’s music that matured gradually over the years.

Have you held or planned any concerts or other projects following the album release?

Shortly after the album was released, we performed at the 34th Akbank Jazz Festival. That concert was a special moment. It was the first time we shared the album live with an audience after the recording.

Following the album, we’ve also been working on a new project that reimagines Zenith in a trio format. In this new approach, we’re rearranging the pieces within a trio setup featuring synthesizer, piano/keys, guitar, and drums—creating a more electronic and contemporary sound texture. Essentially, it’s about revealing another side of Zenith, both structurally and sonically.

We’ve already performed this project in a variety of venues, and we’ll be recording it soon. Sharing this second face of Zenith and showing that it can exist through a different form of expression is something we’re very excited about.

Finally, is there any message you’d like to share with listeners about the album, or anything else you’d like to add?

Each piece on the album has its own character and its own story. That’s why I encourage listeners to approach the album with open ears—not just focusing on a single point, but taking in the whole. Every piece contains not only emotional or symbolic expression but also ideas we’ve worked on over time—concepts that have contributed to our musical development. So, it wouldn’t be wrong to say that the album emerged through a certain systematic way of thinking, both in terms of structure and performance practice. In this sense, I believe Zenith has a layered nature that invites discovery.

One of Zenith’s most important aspects is also a key element of jazz: interplay—the interaction between musicians. Music doesn’t come solely from individual contributions; it’s shaped by the relationships and sensitivities that arise in the moment. Listening to the album with this interplay in mind might allow the listener to uncover different layers of meaning.

Beyond all this, it’s also important to remember: at a certain point, every album, every work of art, leaves the hands of its creator and begins its own journey. It gains new meanings in the listener’s mind, imagination, and life experience. No matter what you, as the artist, intend to say, the music no longer belongs to you. It becomes what the listener hears, feels, and connects with.

As difficult as it may be to accept, this is perhaps one of the most powerful aspects of art: a process of creating a space that cannot be controlled or directed, yet remains completely genuine. And sometimes, that space can form unexpectedly deep connections—even ones the artist never anticipated.

To dive deeper into Barış Arslan’s music and creative journey, make sure to explore the links below. His work extends far beyond this interview—and there’s so much more ahead you won’t want to miss.

Website: barisarslanmusic.com

Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/@barisarslanmusic

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/artist/7gKh8iFgFIPvnvbmIypIh2?si=AL2_IU0PSIW_wmXgyi6_AQ

Apple Music: music.apple.com/tr/artist/barış-arslan/1124220756

Instagram: instagram.com/barisarslanq

If you enjoyed this interview, you might also like 7 Must-Hear Albums for the Ultimate Road Trip Playlist.